Be musically creative by

exploring possibilities with

Melody & Harmony & Rhythm,

and with Cooperative Improvising.

The Wonders of MusicYes, music is wonderful. It's enjoyable and beautiful, can be fascinating and dramatic, familiar and mysterious, relaxing and exciting, inspiring us mentally, emotionally, and physically. Music is one of the best things in life. I'm hoping this page will help you increase your enjoying of musical activities, whether you're just hearing music or you also are making music. { scientific discoveries: music produces many benefits – mental, emotional, physical – when we listen to it or make it. }experiments produce experiences:

|

some history: My original BIG PAGE is now split into two parts:

• this page has “added value” content that is not in my newer pages,

• an appendix-page has ideas that usually are better in the new pages.

how to use this page: Why is an explanation necessary? Because this page is different. Most websites about “making music” have multiple web-pages, and each page links to other pages. By contrast, this web-page IS my website. In this page, many of the full-length sections would be a full page (in the usual kind of music website) but instead I've put all sections into one page. Although this structure isn't the common way to build a website, it offers benefits when it's used effectively. How? When you use a website, you choose the pages you will read. You can use this “website page” in the same way, by choosing the sections you will read. One practical reading strategy is to use the detailed Table of Contents. Also, two of my new pages about improvising music — focused on the educational goal of "helping more people (especially seniors and K-12 students, the old and young) increase their enjoying of music by making their own music" — have high-quality summaries. |

|

|

|

detailed Table of Contents Below, each paragraph describes ideas in the full section (later in the page) with summaries that are fairly brief, but are long enough to explain the main idea(s), so... • you will get a quick overview so you'll understand the main ideas in the page, and • you will know what the section-topic is, to help you decide whether you want to click the link and read {the full section}. You can read the page-sections in any order you want, to explore possibilities for making your own music. The Wonders of Music: It's enjoyable and beautiful, is one of the best things in life, whether you're just listening or also are playing. {and there are benefits: mental, emotional, physical.} {the full section} Experiments produce Experiences so you can Listen-and-Learn: Your experiments produce experiences that are opportunities for learning. The main way you will improve your improvising is learning by doing, when you do musical experiments (you try new musical ideas) to produce new musical experiences so you can listen-and-learn. You will learn more effectively, and more enjoyably, when you use strategies to guide your experimenting — by playing... often slow-and-free (because having time allows creativity) but sometimes faster-with-rhythm (to develop disciplined rhythmic skills), while thinking about theory and by not-thinking, seeking new adventures, expecting to improve, aiming for quality in learning & performing — so you will get more musical experiences and learn more from your experiences. {the full section} Playing by Ear (and Improvising): Instead of “reading sheet music” you can “play by ear” to translate your musical ideas into musical actions. Improving your playing-by-ear skill (when you don't change a melody) will improve your playing-with-improvising skill (when you do change a melody, or you invent your own melody). {the full section} Three Ways to Play By Ear (and Improvise): When you can skillfully sing (with words or without words) or play an instrument, you have an effective connection between thinking and doing, with intuitive-and-automatic translating of your musical ideas (that you are imagining, consciously and/or subconsciously) into musical actions and musical sounds. {the full section}

Theory and Creativity are Mutually Supportive: Originally I tried to split the page into Part 1 (focusing on Creativity) and Part 2 (mostly about Theory). But these efforts – in “trying to split” – were failures, because the more I wrote about musical activities that stimulate creativity, the more I recognized that creative Music-Making usually involves Music Theory, with creative melodies usually involving harmony that is guided by music theory. Therefore the page now doesn't have a Part 1 and Part 2. But some distinctions remain; the sections that are mostly about Musical Creativity have YELLOW BACKGROUNDS, while sections that also emphasize Music Theory are in BOXES WITH BORDERS, ☐. I say "mostly" and "also" because creativity and theory are not mutually exclusive, instead they're mutually supportive. There is plenty of overlap — with theory being used creatively, and creativity occurring in the context of theory — so instead of creativity OR theory, it's more musically productive to think about creativity-AND-theory. {the full section} |

|

Musical Imagery: While you're playing or singing, think-and-feel (for yourself) and/or communicate (for others) your musically-metaphorical “imagery” for the atmosphere-character-flavor-mood of the music, for the ways you're thinking & feeling. {the full section} Musical Mystery: Usually, music that is interesting and enjoyable is semi-predictable, with some surprises. Why? Because when we hear music, we intuitively follow the flow of what has been happening, and “predict” what will happen. If there is too much sameness, we become bored. But we get frustrated if the music is too difficult to predict. We tend to enjoy an in-between mix, with frequent confirmation of expectations along with some surprises, in a blend that is interesting rather than boring or frustrating. {the full section} Musical Tension: In the music we enjoy, one aspect of artistic semi-mystery arises from creatively mixing consonance (sometimes) and dissonance (other times). To do this, a common strategy is moving away from the home-chord (or home-note) of a key, and then returning to it. In this way and others, musicians can produce tension (in their chords and/or melodies) and then resolve the tension. {the full section} Musical Harmony: We think music sounds “harmonious” when certain notes – like those of a major chord or minor chord – are played simultaneously in a chord (this happens due to the interactions of musical physics with human physiology) or (due to this physics-and-physiology plus memory) are played sequentially in a melody. Much of this page is designed to help you use music theory to guide your music playing, to help you play harmonious melodies. / Why do we hear harmony? A perception (in our human physiology) of perfectly-consonant harmony occurs when some overtones of two musical tones (in their musical physics) are perfectly-matched. { In the music we usually hear, why are most harmonies intentionally imperfect? } {the full section}

Improvising Music by doing creative experiments with its Melody, Harmony, Rhythm, Arrangement: Melodic Improvisation: You can play a melody as-is with no changes, or – because the original is just one of many similar melodies – modify it: add or delete notes, change some, emphasize them differently (than in the original), change the rhythm, or... do whatever you want to modify the old melody and invent a new melody that's your variation on its theme. / Or invent a new melody by using harmony. Or with unstructured free creativity, just “put notes together” in any way you want. {the full section} Harmonic Improvisation: You can harmonize with a melody by playing non-melody notes that combine with the melody notes in ways that sound pleasantly harmonious. And invent a harmonious melody when your melody-making is guided by harmony. { colors can help you learn theory and make harmonious music } {the full section} Rhythmic Improvisation: Do creative experiments with rhythms. When you're playing a melody, use more notes (faster, shorter) or fewer (slower, longer); mix fast & slow; split notes un-evenly (as in a swinging “shuffle” rhythm); slide from one note to another (as with a trombone or steel guitar); “do different things” for on-beats (1 & 3) and off-beats (2 & 4); make the tempo slower or faster, or (as with Chopin) variable. And use some silence, with on-and-off sound, by not playing constantly. Do things that are interesting, and have fun. {the full section} Cooperative Improvising (and Arranging): When you're cooperating with other musicians to “make beautiful music together” you can enjoy the interactive process and the musical results. When individuals are creatively coordinating their “yes and” contributions, are responding with mutually supportive empathy, the group is building synergistic teamwork that is musically productive, and fun. / While you're playing, an important responsibility is “playing through whatever happens” to help sustain continuity, to keep the music flowing. / If the musical coordinations are pre-planned, it's called arranging. Appreciating the artistry of an arrangement – as in decisions about the blend-of-instruments that play in each part of a song – is one reward for your Active Listening,... {the full section} Active Listening: You can enjoy “the wonders of music” by just listening. And also with active listening, by using your ears-and-mind to be an aware observer, to perceive more of what's happening in the music. By listening actively you can learn a lot while enjoying the music and your process of discovery. One useful approach is whole-part-whole, with analysis & synthesis, by studying parts and asking how each part contributes to the whole. For example, we can ask “what factors give a musical style its identity, helping it sound distinctive?” / Why are “influences” important, and what are the connections between knowledge & creativity, when we use old ideas creatively by modifying them or by combining them in new ways? { creative songs for active listening, for enjoying and learning } {the full section} Cooperative Improvising – Part 2 : Improvising with a group goes beyond Active Listening because now you're making real-time musical decisions. You can gain experience in private (by playing along with a recording of the group) and in public (by playing with the group). Talk with others during a session (and before & after), asking “what do you think about what we've been doing, and want to do?” During a song, listen actively, think creatively (about your options for helping the group make music), wisely evaluate your options, make quick decisions (to keep the music flowing), and enjoy whatever happens. {the full section} Improvising and Composing: Sometimes improvisation leads to composition, when a musician really likes a particular melodic improvisation so they continue improving it until they decide to preserve it (with writing or recording) as a composition that can be repeated later. Basically, improvising is quick composing that's done in real time; and composing is slow improvising (done over a longer period of time), is slow-motion improvising. { Many famous classical composers – Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and others – were skillful improvisers. } {the full section} Using a Musical Instrument: You can make music with your internal instrument (by singing, with or without words) or an external instrument. Do experiments with your instrument, “try things” to explore its possibilities, to discover how it allows & inspires musical improvisations,* and take advantage of these features. If you play different instruments, improvise with each and compare the results. {* e.g. What is different in its “easy keys” and “tough keys”? } {the full section} a general principle, useful in all areas of life: Whenever you discover something that helps you “do it better” (as in my observation that singing-without-words helps me improvise more effectively), take advantage of the opportunity to improve yourself. Preparing to Improvise: I compare two definitions of improvising — “to invent with no preparation” (this isn't what you want) and (yes!) “to invent variations on a melody or create new melodies” — and recommend one because high-quality improvisation, in music and in other areas of life, requires long-term preparation to build a solid foundation of skills (learned from experiences) if you want to fully develop your mental-and-physical potential. { Effective planning – that includes preparation, and planning to improvise – is illustrated by Vin Scully. } {the full section} Improvising in Life: The ability to effectively improvise – by using principles from music improv plus the “yes and” of comedy improv – is useful in all areas of life, for conversational improvisation and many other practical applications. {the full section} Ideas from Other Teachers: I have great respect for other music educators. They have taught me a lot, and you also can learn from them. I've discovered many excellent educational resources on the web – made by excellent music teachers who are sharing useful ideas – and I'm linking to some of their web-pages and videos. {the full section} |

|

Learn Theory, and Play Music by making Harmony-Guided Melodies {the sections}

When you play only red notes — by either seeing them on a colorized keyboard, or finding them for your instrument — everything you do will sound good, will sound harmonious because the red notes are the chord notes of a harmonious chord. To make your music more interesting, play mainly red notes but also some non-red notes, both white and black. Then alternate time-periods of only red with times of only blue and only green – doing experiments to produce many different chord progressions – before you move onward to alternating mainly red with mainly blue and mainly green. And you can hear multi-red (and multi-blue, multi-green) by playing two or more red notes at the same time, with alternating of colors.

[[ The rest of this section has been moved into the Appendix-Page. ]] |

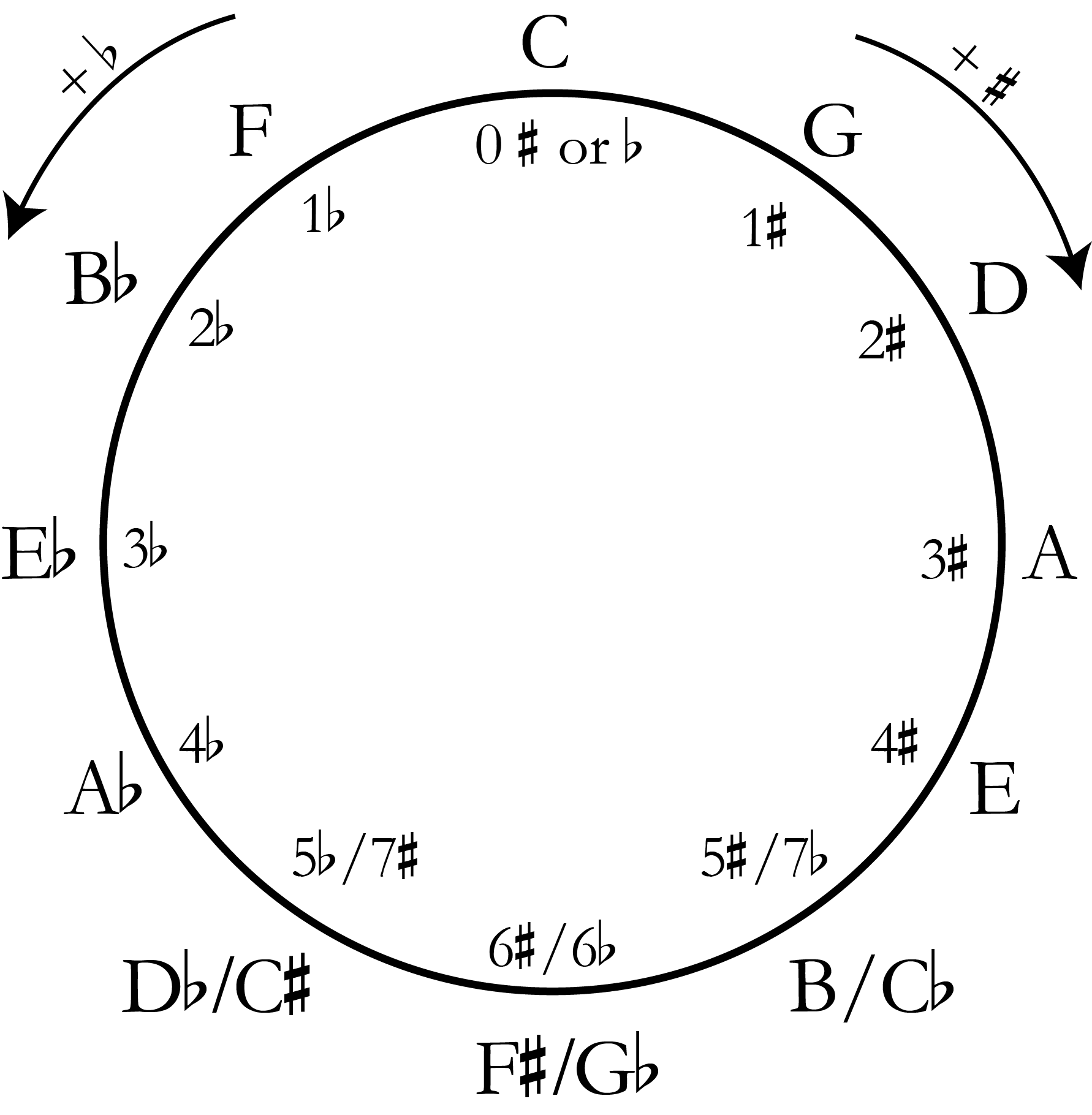

iou – Soon, maybe in April 2025, I'll finish writing this box.Although these summaries are small, each set-of-sections is fairly large, with plenty of useful information. Improvising with Chord Progressions: [[ improvising with chord progressions (with 12-Bar Blues & 50s Progression & more) ]] -- these sections probably will be moved into a separate page, and I'll suggest that you read newer versions in my Summary Page and Details Page; but "more Music Theory" (below) will remain in this page, because it's more thorough than anything in my new pages. more Music Theory: [[ later, maybe in July, I'll summarize ideas from the "more" that supplements earlier Music Theory, with more about major & minor & modal & chromatic & pentatonic, all with octaves — plus The Circle of Fifths. |

Below are the full-length sections that are

summarized in a detailed Table of Contents.

The Wonders of Music: This page begins with appreciation by recognizing that "music is one of the best things in life... whether we're just listening to music or we also are creatively making music." IF I was forced to choose, instead of listening to only my own music I would rather hear only the higher-quality music made by other people, in the creative combinations (of melody, harmony, and rhythm, plus arranging) they have cleverly invented. {some examples} Fortunately this IF isn't an either-or limitation, so I enjoy their music and (even though the quality is lower) my music. Both kinds of music are sources of joy, in different ways. |

experiments and experiences:

|

Make Your Own Music: Play By Ear and Improvise Whenever you sing or play (with others or by yourself), you can either read sheet music (so you are translating the visual symbols into your musical actions) or play by ear (when you are translating your musical ideas into your musical actions) to make your own music. Because this page is for improvisers, it emphasizes playing by ear, which you can do in many ways: While you're listening to a song, sing along (or play along) by singing the melody as-is (so "your musical ideas" match those of the song's composer) or by changing it in any way you want,* or by “accompanying the melody” harmonically and/or rhythmically. Or when you're alone in silence, without a song playing, you can sing a melody “from your memory” or you can invent your own melodies, by playing a keyboard and in other ways. * When you're playing a melody by ear and you play it as-is with no changes, are you improvising? No.* But even when you don't change it, the melody is your musical idea because it's originating inside you – it's coming from your memory of the melody or your imagining of the melody – and you are playing by ear because you are not reading the melody from sheet music. {* although you are not improvising while you're playing a melody as-is, you are playing by ear, and this is musically valuable because improving your playing-by-ear skill will help you improve your improvising skill } Three Ways to Play By Ear (and Improvise) 1a) sing: When you become comfortable with singing, it's a great way to improvise, to make your own music, because it's an efficient connection between thinking and doing, with easy intuitive-and-automatic translating of your musical ideas (that you are imagining, consciously and/or subconsciously) into musical sounds. 1b) sing without words: When I want to modify a melody,* I find that when singing “tones without words” – or playing kazoo – it's easier to intuitively release fresh new ideas, with creative musical ideas tending to happen more often. Therefore I do this (the essential action) and also (with an optional question) ask “why?” / * If I want to sing a familiar melody as-it-is with no changes, singing it with the lyric-words is easy and works well. But to modify the melody, singing without words – just beginning each note with “d” – is better; this simplicity (in my language) promotes complexity (in my improvising). Of course, ymmv; I've observed this happening with me, but you may find it easy to improvise while you're singing-with-lyrics. / Although “singing without words” is still singing, for me it's so different that I can consider it to be a different way to play, a third way, thus 1a and 1b. 2) play a musical instrument: If you play an instrument with skill, this will help you improvise with skill, because (as with singing) your instrumental skill gives you an easy-and-automatic translation of musical ideas into musical sounds. a useful general principle: Whenever you discover something that helps you “do it better” (as in my observations of singing without words), take advantage of the opportunity to improve yourself. more – using the special features of different instruments

Table of Contents |

|

Originally, for two decades the page began by explaining that...

This page has two parts, with useful ideas about Being Creative and Using Harmony: Part 1 — psychological principles & musical activities, for stimulating creativity, Part 2 — logical principles of music theory, for making music by using harmony. But later this was changed. Why? Because the more I wrote about "musical activities for stimulating creativity," the more I recognized that creative Music-Making Activities usually involve Music Theory, with creative melodies usually involving harmony that is guided by music theory. Therefore in most of this page the two parts – Being Creative and Using Harmony – have been blended together, so they're now two aspects of making music, not separate parts of the page. But there is some distinction between these two aspects; page-areas that are mostly about Musical Creativity are in YELLOW BOXES, while page-areas that also emphasize Music Theory are in BOXES WITH BORDERS, ☐. I say "mostly about Musical Creativity" and "also emphasize Music Theory" because creativity and theory are not mutually exclusive, instead they're mutually supportive. There is plenty of overlap – with theory being used creatively, and creativity occurring in the context of theory – so instead of creativity OR theory, of course (as you already know if you have much experience with music) it's more musically productive to think about creativity-AND-theory. |

Using a Colorized Keyboard toLearn Theory and Make Music[[ Most of this section has been moved into the Appendix-Page. ]][[ But I think the sections below give "added value" so they remain here. ]]

play only black notes (in pentatonic scales) Just play any way you want, listen and learn. You don't need to worry about “making a melodic mistake” because everything you do will sound fairly good, so you can just relax and try different ways of playing with the notes. But while you're experimenting and listening, you'll find that some sequential combinations are more useful (for purposes of enjoyment, personal expression, aesthetic appeal,...) so listen for these combinations, and have fun exploring the possibilities. Do musical experiments (do something different) by playing with a variety of melodies, rhythms, and moods. {imagery – imagining a lotus pond at sunset} home-notes: A musically interesting way to explore is by using one kind of black note as a “home note” for your melodic wanderings. How? You can “play musical games” by starting with it, using it a little more often in your melodies, and ending with it. / After awhile, shift to another home note, and you'll be playing in a different pentatonic scale, with a different 5-note pattern. { penta means five, first in classical Greek, then in Latin & many other languages. } discovering patterns: Below, do you see a 5-note pattern that repeats? And other repeating patterns? How many different patterns can you find? { a hint: There are five patterns. Each of these is a different 5-note scale. }  seeing the five scales: When you study the keyboard's black notes, probably the first spatial pattern you'll see is the “group-of-2 and group-of-3” that repeats every 5 notes. And there are other patterns; if we call the first pattern “2-3” the others are 1-3-1, 3-2, 2-2-1, 1-2-2. These five patterns (each beginning with a different home-note) form five pentatonic scales. Each scale has five scale-notes. And then another set of 5 scale-notes, beginning with “essentially the same note” an octave higher, so it is (they are) also “the same home note(s),” i.e. they are in the same group of home-notes.* And then another 5, and so on, in the repeating pattern. { another way to “see” and “mentally visualize” the 5 kinds of black notes } {* Why am I mixing singular-it with plural-they, and describing home-note(s)? } playing with a scale: You can play “play musical games” by doing experiments with the 5 notes of a pentatonic scale. How? One musical strategy, among many possible, is to choose one kind of note as the homenote(s) and “emphasize” this kind of note by starting on one of them and occasionally returning to it (or them) — by playing “below it & above it” or “between them,” moving leftward or rightward, playing all black notes or skipping some — and ending on one of them. / Then change from one scale (with its home-note) to other scales (with other home-notes), and listen for the different “sounds” of the scales.* Is there one (or two) that you think sound especially interesting and pleasing, thus more musically valuable? { two commonly used "musically valuable" pentatonic scales } / * A simple way to compare "the different sounds of the scales" is to play a scale — by starting on the scale's home-note and playing the next 4 notes to its right, then returning downward with another 4 notes — and then play this up-and-down scale when using the home-note of another scale, while listening to their sounds. Or compare only the 5-note ascending scales; or only the descending scales. a common term with two meanings: A scale can mean either a collection of 5 scale-notes (that can be played in any way)* or – with a narrower definition – playing all of the 5 scale-notes in consecutive sequence (without skipping any) beginning on a home-note and ending on a home-note. These meanings are used above in the long paragraph's beginning & ending; and even in the same sentence, if you "play this up-and-down scale" in "another scale." * different kinds of scales: These pentatonic scales have 5 notes, but a major scale has 7, a chromatic scale 12, a blues scale 6, and there are other kinds of scales, plus modes. And all can occur in 12 different keys; e.g. we can play music by using a C Major Scale (in the Key of C) or a D Major Scale, or 10 other scales. singular-yet-plural: Yes, these are different, so my mixing of these — as in "home-note(s)" and "it (or them)" and in other ways — is grammatically illogical. But it's musically logical because we think octave-notes are “essentially the same note(s)” when we hear them as isolated notes, although maybe not when they're heard in the context of other notes. visual simplicity: In each of the five pentatonic scales, all notes that are black – no more, no less – are in the scale. Therefore it's easy to intuitively-instantly-correctly know all notes that ARE in the scale (they're black) and ARE NOT in the scale (they're white, are non-black so are non-scale). This visual simplicity lets you focus your full attention on how you want to use the black notes for creatively making music. / Visual simplicity also is rewarding (musically & personally) when using a colorized keyboard for Using Harmony to Make Melodies. play only the white notes: As with playing only the black notes, for awhile "just play any way you want, listen, and learn." Then try using different notes as a home note, and listen for the different “musical sound” with each home-note. Are there any that you think sound especially interesting and pleasing, thus more musically useful? { home-notes for major & minor and 5 other musical modes }

Discovery Learning for Music Playing – Part 2

[[ The rest of this section has been moved into the Appendix-Page. ]] |

Confidence and Creativity iou – Soon (maybe in late 2024) these ideas will be moved into other parts of the page. The basic self-limiting “games” – when you simplify your options by playing only black notes or only white notes – can be especially useful for novice improvisors, to increase confidence and stimulate creativity. But even if you're a fairly expert musician and/or improviser, you can get useful benefits from these games, because the self-limiting simplifications can encourage creative experimenting, to promote new kinds of experiences that will help you learn and improve. When you play only black notes – especially in low-risk situations – you can be confident because with a pentatonic scale you cannot “make a melodic mistake” so it's easier to do relaxed experimenting. And the limitations — when you use only 5 notes instead of 7 or 12 — can force you to focus on the creative challenge of making interesting melodies by using only these 5 notes; basically, it's “doing something different” and this can stimulate creativity. And for a novice, some ways to “limit yourself” — e.g. by alternating mainly red-dot notes (but also others) with mainly blue-dot notes (but also others) with mainly green-dot notes (but also others) — will actually EXPAND the range of “what you now are doing” beyond what you previously were doing. In this way the game-limits can actually help you to stop repeating your old self-limiting habits, to escape from old ruts by trying something new. And you can discover other ways to reduce your self-limitations, to let yourself break out of a rut by reducing your assumptions about “how you should (and shouldn't) do it” so you can creatively respond to situations in new ways that are non-habitual, that differ from “how you've always done it.” |

colorizing a keyboard – why and how Why? The main benefit of colorizing with red-blue-green (for 1-4-5 chords) is to give you... Easy-Intuitive-Instant Recognition: Making music with a colorized keyboard is easy and intuitive. Why? Because you KNOW, easily and instantly, when a note IS among the chord-notes you want to play, or ISN'T. This easy-intuitive-instant recognition – plus the simple linearity of a keyboard, and its black/white keys – lets you focus your full attention on how you want to use all of the notes – whether they're in the chord, or not – for creatively making music. For example, • When you want to play in the key of C Major, by seeing the colors you will instantly know the chord-notes for the three common chords (C Major, F Major, G Major) and also for the minor chords (A Minor, D Minor, E Minor) because they're all of the white notes, no more and no less. And you will instantly know the non-scale notes (because they're black) that you can use for adding chromatic spice to your melody. • When you want to play notes that will harmonize with a C Chord, you will easily-and-instantly know the chord notes, because they're all of the red notes, no more and no less. And you will instantly know the non-chord notes (all notes that aren't red) that you can use to add non-chordal spice to your melody. What? You can play in C Major and A Minor, because this color-coded keyboard*  works for the key of C Major by showing the chord-notes for C-major (C E G, red) and F-major (F A C, blue) and G-major (G B D, green), for the 1st and 4th and 5th notes in the scale of C-Major (C - F - G) in red - blue - green:  And it works for the key of A Minor by showing the chord-notes for A-minor (A C E, red) and D-minor (D F A, blue) and E-minor (E G B, green), for the 1st and 4th and 5th notes in the scale of A-Minor (A - D - E) in red - blue - green:  * This Music-by-Color Improvising System was invented by me in the late-1970's – when I used it for a melodica – with Copyright ©1998 by Craig Rusbult, all rights reserved. { why 1998? because I first “published it on the web” in 1998. }

Some Pros & Cons of Playing With Colors two kinds of keyboards: If you play on a non-colorized keyboard (without red, blue, green) or in a key other than C Major or A Minor, you won't have the easy-instant-intuitive information that's provided by colors. Probably (almost certainly) this will reduce your playing skill, your ability to fluently make beautifully interesting melodies. So is this a disadvantage of using colors? I think the answer is... yes and no: It's yes (in the short term, temporarily) but no (in the long term). And even in the short term, it's only a relative disadvantage, because your skill will be lower when using a non-colorized keyboard, IF we measure this skill relative to your skill when using a colorized keyboard. But with a broader short-term perspective, your skill on a colorized keyboard probably will be higher than it would have been if you had never used color-cues. Some of this higher skill will transfer to playing on a non-colorized keyboard, and – even though your “non-colorized skill” is lower, relative to your “colorized skill” – your “non-colorized skill” will be higher than it would be if you had never used a colorized keyboard. two strategies: • If you want to increase your transfers-of-skills from a colorized keyboard to a non-colorized keyboard, you can shift back & forth between them. • Or you can just decide “I want to invest my playing time in developing higher levels of skill with a colorized keyboard, and if I ever play on a non-colorized keyboard I'll just accept the fact that my short-term skill (without colorizing) will be temporarily lower – relative to my long-term skill (with the benefits of color-cues) – and I'll use a colorized keyboard whenever it's possible.” specializing in two keys: When you use a colorized keyboard, you can develop higher levels of skill if you invest your playing time by playing only (or mainly) in two keys, C Major and A Minor. Because you're playing a lot in these two keys, your skill will increase a lot. You don't really need to play in other keys, because almost all electronic keyboards let you transpose from one key to another by simply pushing a button.* This lets you develop a level of skill in two keys (1 major, 1 minor) and instantly have skill in the other 22 main keys (11 major, 11 minor) by transposing, by just pressing a button. { In reality, you should know more than two keys, because for playing in C it's useful to also know F and G; plus C Minor; and to play well in A Minor, it's useful to also know D Minor and E Minor.} / Of course, you can "specialize in these keys" without colorizing, but you won't get the benefits of easy-and-instant recognition. efficient use of time: In this way you can focus your attention on learning how to play well in the key of C, since you don't have to learn how to play skillfully in many other keys, including (if you want to master all keys) C# with its 7 sharps. If you don't specialize, your practicing time must be split between the colorized keys (C Major, etc, plus A Minor, etc) and other keys. You have limited time – and “time is the stuff life is made of” (Ben Franklin) – so you can use your valuable time to become highly skilled in only C Major (and A Minor) yet make music in all keys, by taking advantage of electronic transposing. novices and experts: While writing the sections above, I'm mainly thinking about novices or intermediates. The situation (re: pros & cons) would be similar for experts, but a little different because they already know the music theory (implicitly and/or explicitly) and they have experience-and-skill with playing in many keys, including the “specialist keys” (of C-Major & A-Minor) and also other keys. So they might be less interested in the benefits of colorizing. * I wish keyboard-designers would provide a second way to “press buttons” and transpose into other keys. How? By making a sharp-adding "up button" that changes the current key to a key with one-more-sharp (e.g. changing from C to G, then from G to D, from D to A, and so on) plus a flat-adding "down button" that changes the current key to a key with one-more-flat (e.g. changing from C to F, then from F to Bb, from Bb to Eb, and so on). / Why? Here are two reasons: • This feature would be useful for making key-changes within a song, for musical reasons. • And for "playing along" when you don't know the key; for example, if you begin playing and discover yourself playing F# and C# and G# to make your melody sound good, you can push the "up button" 3 times, to get transposing that lets you hear your music in the Key of A (that has these three sharps) even though you're "playing the red-blue-green" of C Major; but if you must play Bb and Eb in your melody, probably you should push the "down button" twice so you will hear the Key of Bb (that has these two flats) while you're "playing in C Major." {keys with sharps & flats, and the Circle of Fifths} [[ iou – Soon, maybe in December 2023, these three grayed-out paragraphs will be "worked into" the paragraphs above. [[ Obviously, this colorized keyboard works best for playing in the key of C-major or A-minor. To play in another key, either ignore the dots or — it's my preference, and I suggest it because I think it's a much better musical strategy — use the transposing feature (available on almost all electronic keyboards) to shift every note you play up or down by the same amount. [[ For example, you can play a melody in the key of C, and then press the button for +1 transposing (which shifts all notes up by one semi-tone, from C to C#) so when you play the same melody (by using the same keys as before) you'll be playing in the key of C# with every note automatically increased in pitch by one semitone. my conclusion: We have logical reasons to expect that, for most people, using colorized keyboards will improve their musical skill. (and musical enjoying)

[[ The rest of this section has been moved into the Appendix-Page. ]] |

|

MUSICAL IMAGERY While you're playing or singing, try different moods, feelings, and images. Some imagery from O. Henry: "As Whistling Dick picked his way where night still lingered among the big, reeking, musty warehouses, he gave way to the habit that had won for him his title. Subdued, yet clear, with each note as true and liquid as a bobolink's, his whistle tinkled about the dim, cold mountains of brick like drops of rain falling into a hidden pool. He followed an air, but it swam mistily into a swirling current of improvisation. You could cull out the trill of mountain brooks, the staccato of green rushes shivering above the chilly lagoons, the pipe of sleepy birds." And from Jeremy Grimshaw: "In the 1930s (and, arguably, still today), musical exoticism evoked the sounds of a place removed by imagination rather than distance. Ellington's "Caravan," in its various instantiations (or even in individual versions) seems to noncommittally wander across various landscapes, from Iberia to the Silk Road, from the desert to the tropics; the sounds of Tizol's native Puerto Rico mingle with notions of a distant Arabia. Ultimately, however, the angular melodies primarily serve to extend the musical palette, an expansion of expressive possibilities metaphorically reinterpreted as an exploration of unknown lands." { He also vividly describes the song's musical artistry. } And you can invent your own imagery. One of mine is to imagine sitting at the edge of a small pond filled with floating lotus blossoms in China, watching a beautiful sunset and playing music – on a bamboo flute with pentatonic notes – that fits the mood I'm imagining. {the bamboo flutes I made have 5 notes for pentatonic-scale playing, or 10 notes for major-scale playing} Of course, the people we know often inspire art, including music. In one example, Duke Ellington's brilliant Sophisticated Lady was inspired by three of his grade-school teachers, who "taught all winter and toured Europe in the summer," who influenced the moods, feelings, and musical imagery we hear/feel in the song inspired by his fond memories of these sophisticated ladies. When you're playing or listening, you can use imagery for the music, or for the way you're feeling or thinking. Or you can imagine (by thinking “classical” or “blues”) that you're playing in a musical style that is a “classical-sounding style” or “blues sounding style” while improvising with a chord progression. MUSICAL MYSTERY In his book, Emotion and Meaning in Music, Leonard Meyer describes our musical expectations by proposing that when listeners hear music they intuitively follow the flow of what has been happening in the music, and they unconsciously “predict” what will happen. If there is too much sameness, so listeners can predict everything, they may become bored. But they may get frustrated if the music is too difficult to predict. Usually, the music we enjoy is an in-between mix, with some confirmation of expectations along with some surprises, in a blend that is interesting rather than boring or frustrating. These ideas are explored in my page about Mystery in Music that asks why we don't necessarily become bored or frustrated: For example, you enjoy hearing some songs over and over, even though (or because?) you already know what will happen. And you can enjoy listening to innovative music that is difficult to predict, when it fits together in a creatively logical way (like a clever mystery story) so you can think back on what you've heard and say “yes, of course.” Or maybe you think “I'm not sure why, but it worked” and it made an entertaining musical experience, with music that was unusually beautiful, maybe peaceful, or maybe edgy, zany, energetic, playful,... In drama & humor, dancing & conversation, and other aspects of life, you can think about the functions of expectations that are partially fulfilled, yet with some surprises that “make sense” in retrospect, or that simply add interesting variety. Imagery and Mystery are only two of the many aspects of Emotion that artistic musicians can use when they express what they feel, and want you to feel, while they are playing music. You also can do this, whether the music you're making is your current improvisation or is a previous composition of your own, or from another person. New Knowledge: In the time since 1956 (when Meyer wrote the book) and 1971 (when I read it), musicians & scientists have learned a lot more — in addition to the many things we knew earlier, like musicians using “a theme with variations” to blend familiarity with variety — about relationships between anticipation (during music that's often designed so it produces musical tensions) and resolution (with a resolving of tensions). In modern science, psychologists & neuroscientists have been studying human responses to music, by carefully observing and by measuring with modern technologies. They are confirming, at deeper levels, what we already knew about responses (by you, me, and others) when we're listening to music. Your process of predicting “what will happen” is enjoyable, and so is your mental-and-emotional satisfaction when you hear your predictions being fulfilled. But you also can enjoy the experience of unexpected delight when you're musically surprised in a cleverly interesting way. This response typically occurs at a subconscious level when you're listening to music, but it's similar to your conscious response when you recognize the funny twist in the punchline of a well-designed joke, or the logical twist in the ending of a well-designed mystery story, when you're initially surprised but then you decide “this does make sense, yes it's logically coherent” when you think about the clues in earlier parts of the story. In ways that are similar, you appreciate the creative artistry-of-surprise in the music, joke, or story. Producing-and-Resolving Tension Some of the most important communication between players and listeners involves producing “musical tension” and then resolving the tension. It's one kind of moderate Musical Mystery with some fulfilling of expectations and some surprises. How is tension produced? One cause is when musical improvisation includes non-chord notes — that are not among the 3 notes of a major chord (like CEG) we hear as total harmony-consonance — instead we hear some harmony-dissonance. This dissonance produces a feeling of musical tension, and perhaps even psychological tension. A perception of dissonance can occur when the mixed combination (with some chord notes and some non-chord notes) is played simultaneously in a harmony or is played sequentially in a melody, or if both are happening in the music. But tension also can be produced-and-resolved when a V-Chord (producing tension) is followed by the I-Chord that is the home-chord of the key, for resolution. In this way, tension is resolved even though there is no dissonance in the V-Chord. Some tension also can be produced by using a 7th-Chord that combines consonance (with the three interactions between its triad-notes of 1 3 5) and dissonance (with the tritone interaction between its 3 and b7). This "also" is a co-contributor to a combination that results in a more dramatic resolution of tension, because the tension has two sources — it occurs because V is not the home chord, and because V7 contains dissonance — when both sources are resolved, when the V7 is followed by I (because I is the home-chord, and I is not dissonant). {the structure of 7-chords} Of course, an experience of dissonance is in the ear-and-mind of a listener — who can perceive it as being unpleasant (to some degree) or as pleasantly interesting (this is the usual result, unless it's too dissonant or if the dissonance lasts too long) — depending on the kinds of non-chord notes and their timings. The psychological result for you (as a listener) is a personal response that depends on... the amount of dissonance, whether it's a lot of dissonance — as in the simultaneous playing of almost-unison notes (e.g. with adjacent notes like C and C-sharp) that are almost the same but not the same; or if musicians are trying to play the same notes, but they're not mutually-in-tune (so some are playing a little too flat or too sharp), or with almost-fifth notes (like C and G-flat instead of C and G) that also are an almost-fourth compared with C and F — or is just a little dissonance, and In the music we enjoy, much of the art arises from a creative combining of consonance (sometimes) and dissonance (other times) to produce feelings of pleasant harmonies blended with dissonant tensions. It's one aspect of the semi-mystery (some but not too much) we enjoy during artistic communications between players and listeners. / consonance and dissonance from Brittanica & Wikipedia (with music theory) and others.

|

Improvising Musicby using Melody - Harmony - Rhythm - ArrangingMelodic ImprovisationTwo kinds of strategies for making a melody — with free creativity (by just “putting notes together” in any way you want) and structured creativity (by modifying an existing melody and/or using harmony to make melodies, or in other ways) — are related. How? Because even though “free” and “structured” might seem to be mutually exclusive, in practice when you are making music (and in other areas of life) there are productive connections between memory and creativity. As described in my section about musical styles, creative new music is not totally new, it's just new variations of old music, it's "built on the foundation of music from the past, when old ideas are modified in new ways, and combined in new ways." Therefore the ideas below (and in other parts of the page) can be useful for stimulating creativity that seems to be “free” or is consciously structured. The original melody is just one of many similar melodies, so it can be modified to make a new melody. To begin doing this, play the old song-melody by ear (alone or with others) as-it-is, with no changes. Then to produce “variations on a theme” in a new melody that is related to the old melody,* you can change some of the original notes; or add notes, or eliminate notes; make wide leaps from one note to another; or use closely spaced notes in a scale-notes sequence with pitches ascending or descending, or (with narrower spacing) in a chromatic sequence, or (with wider spacing) a chord-note sequence; or change the rhythm. You can use these possibilities, and others, in any blending you want. * In this strategy for improvising music, the goal is to modify a melody, but not replace it. If a modified melody is too different from the original, it's difficult to hear the connection between old and new, so most listeners will wonder “where did that come from?” because they won't hear it as being a variation of the original melody. Instead a listener will think it's a totally different new melody, with no connection to the old melody. Of course, this is OK if it's what you want. But if you want listeners to recognize that your new melodies are creative variations of the familiar old melody, you'll want to aim for a moderate level of "musical mystery" that is not too low or too high, so listeners won't become bored (if the mystery is too low, with not enough variation) or frustrated (if it's too high, and the original melody cannot be recognized), so they will have "some confirmation of expectations along with some surprises." Whether your improvisational creativity is mostly “free” or “structured” or an in-between mix, you can make melodies by trying to combine notes in fascinating new ways, by doing creative experiments that produce new experiences so you can learn from your experiences. For example, in Sophisticated Lady (by Duke Ellington) the main theme uses notes that often move in small steps, by contrast with the chorus where notes make big up-and-down leaps, yet the two parts (main theme & chorus) fit together well despite their differences; in fact, the contrasting differences add to the song's overall appeal. The entire song, in each part and as a whole, uses notes in creative ways to form melodies that are carefully designed to be unusual yet beautiful. {you can read more about Sophisticated Lady — inspired by memories of three grade-school teachers who taught in winter and toured Europe in summer — and hear its theme & chorus}

Rhythmic ImprovisationExperiment with different rhythms: If you're playing a melody, you can play more notes (faster, shorter) or fewer notes (slower, longer). Or mix fast & slow (short & long) in interesting ways. Or instead of splitting quarter-notes evenly to make two equally long eighth-notes [as in a timing of 3-and-3, if a quarter-note is “6”] you can split them into uneven triplets [4-and-2] to make the music “swing” (as in a “shuffle” rhythm for 12-bar blues).* Or you can slide from one note to another (as with a trombone, violin, steel guitar, or voice) instead of making a time-separation between the notes. And you can “do different things” for the on-beats (1 & 3) and off-beats (2 & 4). {* videos explain the "swing" of uneven triplets in words and music - plus diagrams - on guitar & saxophone. You can make the tempo slower or faster or (as in songs by Chopin) variable, if you are playing by yourself, or are in a group that has a way to “do it together” with coordination. And use silence – it's one artistic way (among many) to produce fascinating mystery – by not playing constantly, with “rests” that let the sound be on-and-off. Inspirations: If you listen to music from a variety of cultures, you'll hear a variety of rhythms, and you may want to use some of these rhythms (as-is or modified) in the music you're making. Cooperative Improvising (+ Arranging)In addition to the basic elements of music – harmony & melody & rhythm – we can enjoy the interactions between musicians who are creatively cooperating so they will “make beautiful music together.” When the musical coordination is pre-planned it's called arranging, with an arranger (the original composer or someone else) deciding what kind of musical blend – with different musicians & their instruments contributing to “the blend” in different ways – will be used in their arrangement of a song. You also are making these decisions “in real time” while you're playing along with other musicians, maybe with some pre-planning, and certainly by listening actively while you're improvising. You'll want to think about the functional role you'll play in the group, by playing chords or bassline, or melody, or...; e.g. this is why a band often has three guitar players, playing lead guitar, rhythm guitar, and bass. [[ iou – Later, this section will be developed more thoroughly. Some ideas that will be used are... creative synergism (as in Habit 6 of The 7 Habits) during cooperative collaboration, teamwork analogies, the “yes and” of improv in comedy & in everyday life. ]] iou – Soon (maybe before mid-2025) I'll develop these ideas: When you're cooperating with other musicians, you want to be consistently decisive in doing something that is rhythmically compatible with what others are doing. Practicing with a metronome – and with “backing track” videos – can help you develop the self-discipline of being rhythmically consistent, of being in-synch with the timing of your fellow musicians. I'll be learning more about this from others (e.g. pros & cons of using a metronome) and then will write about it. If you “play through” perceived mistakes, by yourself or others, you can develop and sustain a continuity (for the melody, rhythm, and harmony) that keeps the music flowing through time. And you can learn for the future, making it better by using the “master skill” of learning from experience. Ben Sidran describes the musical skill of graceful recovery from perceived mistakes, of responding in a way that is musically productive, that contributes to artistry & enjoyment for you, your fellow musicians, and those who are listening. He explains that "You have to fail at something first – which is not a failure, but an opportunity. They say jazz is the music of surprise, because you want to play what you don’t know, which means you have to make mistakes, and then recover from them. Music is the act of recovery."

Table of Contents |

Active Listeningiou - [[ This intro-paragraph will be developed-and-revised soon, maybe in August 2024: The page begins by describing "the wonders of music" and why "I'm hoping this page will help you increase your enjoying of musical activities, whether you're just listening to it or you're also creatively making it." / when you're thinking "wow, this music is ___" or "ahh, ____" where the blank could be filled with whatever you're feeling & thinking. ... however you feel about the music, whatever ___ is. / I also will describe "another kind of listening" you can do, along with this just-enjoying, when you decide to do the "active listening" described in the rest of this section. ]]This is similar to playing along but instead of being active-and-active (by actively playing while actively listening) you are passive-yet-active: you passively let someone else play a song (on a CD, tape, radio, video, mp3,... or live) and you actively listen. Be alertly aware, fully using your ears and mind so you can be a good observer, so you can hear more of what's happening in the music. By listening carefully, you can learn a lot while enjoying the process of discovery, and enjoying the music. At a basic level, you can listen for the rhythm (usually interacting with melody) that produces the 1-count of each musical measure, and decide if the measures have 4 counts (most common) or 3 counts (as in a waltz). At a level that's more advanced, but is easy to hear when you're musically aware, listen for longer-term musical structures that may occur every 4 measures, or every 8, 12, 16,... Whole-Part-Whole Analysis: Your goals, which can change from one listening to another, may be to experience the overall effect of “the song as a whole,” or to focus on specific characteristics of the music. You can shift your perspective back & forth between levels, by using a whole-part-whole approach. For example, after listening to the song as a whole, you might listen to one instrument so you hear the role it plays in the whole, how it relates to other instruments & to the whole, and what functional role it plays in the musical mix. Or choose the “part” in another way. If you want to move from “what is” to “what might be,” try to imagine how some instruments could play their roles differently, and how these changes would affect the overall musical result. [[ iou – soon, maybe in late July, the following ideas will be "worked into" this paragraph: One strategy for the process is whole-part-whole, with analysis and synthesis; you can do this in many ways, by focusing your attention on part of a song, or one aspect of the music, or one musician (asking “how do they relate to other musicians?” and “what is their functional role in the musical mix?”), and by sometimes perceiving “the song as a whole,” shifting your perspective back & forth between the whole and its parts, or by changing your focus from one part to another. Musical Styles: You can repeatedly listen to the same song – and other songs with similar style – trying to hear-and-understand what makes the music what it is. And you can listen to different styles of music, asking “What makes each type of music sound distinctive?” In each style, try to discover the characteristics — the combinations of tempo, rhythms, melodies, harmonies, chord progressions, instruments, playing/singing styles,... — that make the style sound the way it does. You can do this just to appreciate the style, or also to imitate it in your own music, or try to modify it with various adjustments of the characteristics. Memory + Creativity: Instead of being “totally new,” creative new music is just new variations of old music. Skilled musicians often speak fondly, with appreciation, about their “influences,” about the music they have listened to, have enjoyed and learned from. Their musical memories influence (both consciously and unconsciously) the way they now make their own music. They recognize that their creativity does not happen “from zero” in a cultural vacuum, instead it's built on the foundations of music from the past, with old ideas being creatively modified in new ways, and combined in new ways. Cooperative Improvising – Part 2Listen Actively while you are Actively ImprovisingThis is another level of experience – beyond just active listening – because you have opportunities to make real-time musical decisions. When you're beginning, and later, it's useful to "experiment in low-risk situations... to gain valuable experience." How? Some ideas are in Part 1 (and its summary), and more are below:Hopefully you can find a friendly group to play with, and they'll have a supportive “mistakes are ok” attitude that encourages you to relax-and-experiment so you can listen and learn. It's fun to make music together, and your friends can provide stimulation plus feedback that will help you learn. And if non-players are listening, they can provide external “audience feedback” from outside the band. Or you may find it easier to practice in private – at least initially – by playing along with a recording (mp3, CD,...) so you can reduce your concerns about mistakes. Or ideally you'll combine the best of both, live and private, by getting a digital song-file of a group you've been playing with, so you can practice privately between live sessions with the group. When you do this, you're “experimenting in private” so when you “play along in public” your previous learning-from-experience (in private) will help you make better contributions (in public) to the music of your group, and feel more confident & comfortable playing with them. While you're playing along with a group (live or recorded), experiment with cooperative interactions. Try playing various functional roles — by providing a main melody (or variation of it, or harmonizing with it) or a chord structure, bass line, rhythm, or whatever else you think might contribute to the musical mix — so you're experimenting with different ways of playing, of deciding what to play and when. Communicate with group members, asking "what do you think?" about the roles for different members (including you), and how roles might shift during a song. Be aware of the overall situation (for you & your fellow musicians) and the musical details of what they have been doing, are doing, and might be doing soon. Try to play with good taste & rhythmic precision, aim for cooperative creativity-with-quality, and enjoy whatever happens. { the art of being a good musical partner by “playing through” mistakes } Improvising and ComposingImprovising can lead to Composing: Sometimes improvisation leads to composition, when an improviser likes their melody enough to continue developing it so it becomes what they really want it to be, and to preserve it by “writing it down.” This converts their improvisation into a composition that can be recreated later, can be repeated. Regarding their timings, improvising precedes composing and its process is faster. We can think of improvisation as quick composition that's done in real time; and composition is improvisation that's done over a longer period of time, is a slow-motion improvisation.This page begins with experimenting while you listen carefully for feedback, to discover what does and doesn't work well. When you find something that "works well" during a musical improvisation, you may want to preserve the results of your creative discovery in a musical composition so it can be repeated in the same form. When this happens, the status of your music changes from one-time temporary to many-times permanent. Because improvisation is on-the-spot composition, in real time while the music is happening, all skilled improvisers are skilled composers. And some composers, continuing the tradition of J.S. Bach and other classical composers,* are also skilled real-time improvisers, with an ability to perform well and produce pleasing music when they (and their listeners) care about the quality of the music. You can preserve a composition — so it can be duplicated later by yourself or others — by writing it on a sheet of paper or, in modern times, by saving it in the memory of a computer or electronic instrument. Or your improvisation can be recorded on tape or digitally, and then transcribed into a musical composition. Or you can just remember what you did, and then play it (or something like it) later. With continued repetition you'll develop a collection of musical ideas that you can play, and you like to play, and these will become part of your musical repertoire. * According to Wikipedia & Brittanica, "Throughout the eras of the Western art music tradition, including the Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque, Classical, and Romantic periods, improvisation was a valued skill... and many other famous composers and musicians were known especially for their improvisational skills. ... Some classical music forms contained sections for improvisation." & "Many of the great composers of Western classical music were masters of improvisation, especially on keyboard instruments, which offered... virtually boundless opportunities for the spontaneous unfolding of their rich musical imaginations. Many an idea so generated eventually appeared in a written composition. Some composers have regarded improvisation as an indispensable warm-up for their creative task." Their combined list of improvising composers (Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Handel, Mendelssohn, Chopin, Liszt) is impressive, and "many other famous composers and musicians" were skilled improvisers.

Table of Contents

Using a Musical Instrument As described earlier, you can make music by using three kinds of instruments: 1a) use your internal instrument by singing with words: When you become comfortable with it, singing is a great way to improvise because it's an efficient connection between thinking & doing, with easy intuitive-and-automatic translating of your musical ideas (that you are imagining) into musical sounds (that you are actualizing). 1b) use your internal instrument by singing without words: You may find (as I do) that when singing without words – or playing kazoo – it's easier to intuitively release fresh ideas, and new musical ideas tend to happen more often. { why? } 2) play an external instrument: If you play a musical instrument with skill, this will help you improvise with skill, because (as with singing) your instrumental skill gives you an intuitive-and-automatic translation of ideas into music. note: In the common way we use language, musical instrument means an external instrument. But when we're thinking about making music, all instruments (internal & external) share many similarities – but they're musically useful in different ways – so in this page "instrument" means either your internal voice (1a-1b) or an external instrument (2). With any instrument, you can... Explore Possibilities and Make Choices: Every musician can use the basics of music – its melody & harmony & rhythm & arranging – in many ways, in many combinations. Of course, each musician will be able to use only a small fraction of the possible variations, and your choices of what to use (and not use) are an essential part of your art. When you're exploring, one possibility is... Using Simplicity to Increase Complexity: When I sing without words "it's easier to intuitively release fresh ideas, and new musical ideas tend to happen more often." The overall result is that a decrease of singing-complexity (by not using words) leads to an increase of music-complexity. Why is musical creativity increased by the simplicity of singing without words? Maybe it's because nonverbal creativity is being freed from the old ruts imposed by verbal habits (when I continue to “musically remember” the familiar melodies that in my memory are connected with the song's words), so without words the nonverbal musical ideas are less restricted by verbal habits; and because my brain doesn't have to “multitask” by doing both nonverbal and verbal, so I can use more of my mental resources to focus more completely on making nonverbal music; and because ignoring the words makes it easier to intuitively-and-automatically translate my ideas into music; and...? But no matter why it's happening, this works for me, with simplicity allowing a free flow of improvising, with a better stimulating of creativity. And probably this will work for you. More generally, whenever YOU notice a situation – or a personal action – that stimulates your musical creativity (as in my observations of singing with & without words), you can take advantage of this opportunity for creativity. {another strategy for simplicity is to play a keyboard and specialize in C-Major / A-Minor} simplicity and complexity in singing without words: I usually “keep it simple” by just beginning notes with “d” so I can focus on the musical melodies, harmonies, and rhythms.* But sometimes an important part of scat singing (without words) is a creative use of nonsense syllables that can have a wide range of variations — formed by pairing any consonant with any vowel, and combining these pairs in a variety of rhythms — and a singer's verbal complexity is one part of their musical complexity. / * You can hear examples of skillful music with verbal simplicity – by starting all notes with d – in the scat singing of trumpeter Chet Baker. And skillful music with verbal complexity by Ella and Mel & Ella and others. Plus lessons for scatting with semi-simplicity and a little more complexity plus deep dives in playlists by Aimee Nolte for Scat Singing 101 (in 6 Parts) & Next Level (10 Parts + 1) & Series (7 with variety, "what do you think about when you improvise?" and more). the artistic benefits of singing with words: In most styles of music a very important part of a song is its lyrics, especially for verbal communications between musician(s) and listeners that produces “connections” between us, but also because the musical artistry of a singer – in creating “the sound” we enjoy hearing – includes their musical using of words. Of course, with or without words, singing in tune with proper pitch is important. All of these ways to make music – 1a & 1b (with your internal music-maker, your voice) and 2 (with an external music-maker) – are different musical instruments, and you can... Hear the Differences: Each instrument – wind, string, keyboard, percussion,... – is unique in its tone quality and music-making possibilities. Use the Differences: If you play different musical instruments, you can do different things with each, so play with each of them and listen to the differences in results. I play several: voice (by singing, usually without words) and thus kazoo, plus whistling; and playing slide trombone, valve trombone, bamboo flute (that I made), percussion (washboard,...), harmonica (aka blues harp), guitar and keyboard. My favorites are voice, keyboard, and slide trombone. Each instrument inspires different types of musical improvisation, due to differences in... tone (and thus mood & imagery), speed (e.g. valve trombone allows faster playing than slide trombone), flexibility (slide trombone allows musically creative “sliding” between notes as in this example and in sliding with voice, violin, or steel guitar), muscle memory (this will make some note-patterns easy for you to play, but only on a particular instrument), visual thinking (as for keyboard or slide trombone),* and other factors. Creatively experiment with different instruments, including your voice, and explore the possibilities of each; don't limit yourself to what is possible with other instruments, because each music-making instrument allows different types of musical improvisations, and inspires them; do experiments that produce new experiences; observe what happens, so you can listen and learn. Expert players can skillfully adjust the pitches of their instrument (saxophone, trumpet, guitar, or other) for musical purposes that include special effects like the note-bending in many guitar solos, plus a famous clarinet glissando (at beginning of Rhapsody in Blue) and artistic “long sliding” by Urbie Green, and in other ways. / To avoid the intentional dissonance of even-tempered tuning, instruments that can play with just tuning are trombone, steel guitar, strings (violin, viola, cello, fretless bass or guitar), and voice. * Instruments and Keys: Each instrument is easier to play in some keys. For example,... My colorized keyboard helps me use “visual thinking” while playing in the key of C-Major (or A-Minor) and, although with less color-guiding, so does using only the white notes. And it's easier (why?) to play pentatonic music in the 5 pentatonic keys (including G-flat Major Pentatonic and E-flat Minor Pentatonic) formed by using only the black notes. With slide trombone, the key of F allows the greatest variety of “long sliding” options, as explained in my visual-thinking page for trombone. And as one example of "other factors" that affect instruments, with a valve trombone the key of E-flat is easy to play (much easier than E), but with a guitar the key of E (not E-flat) is easier. Options for Adjusting: Being able to play in many keys also is useful for playing along with musicians who are playing other instruments (with different "easy keys"), or who want to play in a key that matches their vocal range. But you can easily change a recorded song into “an easy key” for your instrument by using the free pitch-changing software, Audacity. Or you can mechanically adjust your instrument, while still playing in one of your favorite keys, by using a capo (for guitar) or transposing (for electronic keyboard). Or you can change a song into “difficult keys” to challenge yourself. { Or, in a different area of life, instead of changing a song's pitch to change its key, you can change a song's tempo to make your running more fun-and-efficient. } [[ iou – these two grayed-out paragraphs will be "worked into" the section above: ]] [[ You can learn from your experiences of active listening, and also from playing along with a song so you “hear your musical ideas while they're happening” with your own listen-and-learn experiments: [[ While you're actively listening, you can play along (using your voice or a musical instrument)* with a song from radio, youtube, CD, mp3 or tape, or live with other people in a playfully informal jam session. Play with different songs, to get a variety of contextual inspirations, or repeat a song over & over so you know it more deeply, so you can explore creative options, try a variety of musical ideas and observe the results, adjust what you're doing, and discover new possibilities.

Table of Contents |

Overviews of Improvising:Here are two “big picture” perspectives on improvising.

Preparing to ImproviseFreeDictionary's first two definitions of improvising are: 1) To invent, compose, or perform with little or no preparation. 2) To play or sing (music) extemporaneously, especially by inventing variations on a melody or creating new melodies in accordance with a set progression of chords.Definition #1 is sufficient for low-quality unskilled improvisation, and is necessary if you are forced to “do the best you can” to cope with an unexpected situation. But in many real-life situations that require improvising, you must "perform" in ways that are more important than when you "invent, compose, or perform [music]." High-quality improvisation, in music and in other areas of life, requires long-term preparation to build a solid foundation of skills (learned from experiences) if you want to fully develop your mental-and-physical potential. When you are well prepared, you will never have to face an unexpected situation "with little or no preparation," at least in the areas where you've done preparation. Definition #2, by contrast, accurately describes the kind of musical improvisation that is the focus of this page, that is used by all musicians. planning that includes planning to improvise: This was the strategy of Vin Scully — who justifiably was honored with many awards during his long career as an announcer (mainly for baseball but also football & golf, on radio & television), especially for the Dodgers in Brooklyn & Los Angeles — who would prepare thoroughly before each game, so during the game he could expertly decide “what to say and when” based on what was happening during each inning, each pitch, each play. During times with action he would colorfully describe the action, and during times with minimal action he would colorfully tell stories (about players, history,...) based on his preparation. He planned & prepared, and part of his plan was planning to improvise. Improvising in LifeI.O.U. – Later, this section (about other contexts-in-life) will be a brief overview, plus “more” in an appendix. It will describe principles for productive thinking (or not-thinking) in various contexts, when performing skills that are mental and/or physical, including musical improvisation (music and design) and many other skills (e.g. comedy improv) in many areas of life. For the appendix, I'll find page-links to share, from web-searches like [everyday life improv yes and] or [everyday practical improvisation skills] like conversational improvisation or [improvisation in life].

Table of Contents |

|

Ideas from Other Teachers [[ iou – soon, during August 2024, I'll combine these resource-links with new links I've found. / And from an earlier version of this iou: I'll write an Introduction (a slightly-expanded version of my summary for the Detailed Table of Contents – describing my respect for other music educators, and recommending that you also learn from them, not just from me – and will check these links (to be sure they haven't been "broken" and if necessary, fix them by using The Internet Archive of The Wayback Machine) and will link to additional edu-resources. Recently I've been finding many excellent resources, made by many excellent music teachers, especially in youtube videos, but also in web-pages. ]] Of course, you can learn much more than is possible by reading this page, when you read other pages! (i.e. by reading-and-using ideas from my page and their pages) In a web-search for [music improvisation], for example, I discovered many interesting pages, including these: 11 Improvisation Tips from Michael Gallant,* and 12 Improvisation Tips from Cherie Yurco writing for MakingMusicMag that also shares How to Overcome Inhibitions and Improvise by Christopher Sutton who explains how "improvising can improve your musical ability in many ways," and recommends that you "practice in private" because "the best way to reduce your inhibitions around improvisation is to get familiar with it, and familiarity comes from practice," plus Understanding Scales and Chords (as in my "Part 2" below) by Jon. And you can explore more widely and deeply, to learn more, by using other search-terms, and following links in the pages you find, and by exploring in other ways. For example,... By following a link, I found the website of Rick, who wants to help you learn-and-use principles for improvising jazz. {and other styles of music} He emphasizes the value of playing by ear. Why? He explains how "as I continued to read and learn about great jazz musicians, I found that there is a skill common to all of them. ... That skill is the ability to play by ear. All great jazz musicians can play accurately and effortlessly by ear. And actually, it's this skill that first and foremost guides them in deciding what to play." He appreciates the value of singing — which is useful for playing by ear because "you've most likely been singing songs your entire life, and you've probably done so rather effortlessly. ..... You can effortlessly sing by ear. You simply think about a melody and you sing it. ..... This natural ease we have using our voices should be taken advantage of when learning to improvise" — and of listening because "listening to jazz [or country, rock,...] is the single most important thing you need to do if you want to learn how to play jazz [or country, rock,...]" and he offers tips for listening. And for Ear Training and much more. * Here is a brief overview of ideas from the "11 Tips" article by Michael Gallant. The titles of his Tips are: Believe that you can improvise – Play along with records – Mess with the melody – Mess with the rhythm – Learn music theory – Try reacting to what’s around you – Embrace the accident – Don’t judge yourself in the moment – Review after the fact – Say something – Keep learning. Some ideas from "Play along with records" and "Review after the fact" are: "A great way to get your toes wet, build confidence, and gain experience as an improviser is to jam along with your favorite recorded music. ... finding how your sound and style fits in with the albums you love can take you far. ... Just find a space and time when you’ll be alone, put on some of your favorite music, and make noise that you feel dances nicely with what you’re hearing. Try different approaches – perhaps play... [in each "play" he describes a different kind of experimenting you can try] Similarly, you can try playing... and then play... Most importantly, experiment far and wide, and go by what you think sounds good." And, to learn more from your experiences, "Record your improvs on an iPhone or other handy digital device, note what works and what doesn’t, forgive yourself for any mistakes made, and bring that newfound knowledge to your next opportunity to improvise – you’ll be that much more skillful and assured in your playing the next time around."

Table of Contents |

You can improvise musical melodiesby using Sequential Harmony that is

|

more Music Theory:2A. Scales and Chords,2B. The Circle of Fifths.

A. Scales and Chords (in Music Theory)We'll look at diatonic scales – major and minor plus modal – that use 7 notes, and scales that use more notes (12 in a chromatic scale) or less notes (5 in a pentatonic scale). { you can read these sections in any order you want }

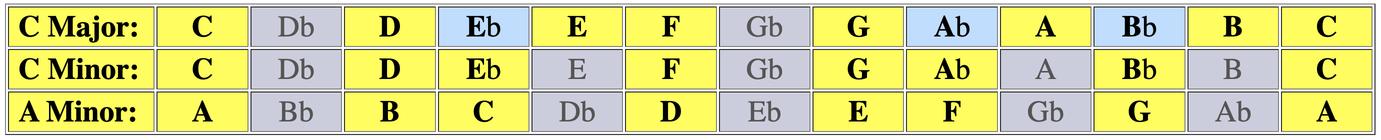

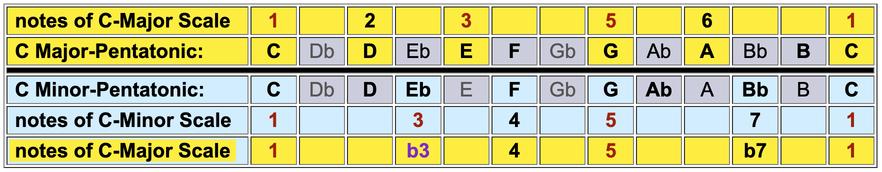

iou – Section A will be updated-and-revised (maybe in June 2024) based on what has been added to my earlier section about Music Theory. The Two Most Common Scales – Major and Minor The scale of C-Major begins on C and uses only the 7 white notes on a keyboard, but none of the black notes. What is the difference between major and minor? In a minor scale, three notes (3, 6, 7) are a half-step lower than in the corresponding major scale; a C-Minor scale is C, D, E-flat, F, G, A-flat, A-flat, C. When you compare the C-major and C-minor scales below, and you'll see a flatted third ( E → E♭), sixth ( A → A♭), and seventh ( B → B♭), C major: C D♭ D E♭ E F G♭ G A♭ A B♭ B CC minor: C D♭ D E♭ E F G♭ G A♭ A B♭ B CThe major scale with no flats or sharps (so it's played using only white keys) is C Major. The minor scale with no sharps or flats (played with only white keys) is A Minor: A minor: A B♭ B C D♭ D E♭ E F G♭ G A♭ AOn a keyboard (or other instrument), listen to the difference when you play a C-major scale and C-minor scale. Then compare C-major with A-minor. { more about minor scales }