What can I learn now? (that will help me in the future)

One reason to learn is a forward-looking

expectation that what you are learning will be personally useful in the future,

that it will improve your life. A good question to ask is, "What

can I learn now that will help me in the future?" For example,

Learning

from Experience (how to excel at welding or...)

One of the most powerful master

skills is knowing how to learn. The ability to learn can itself be learned,

as illustrated by a friend who, in his younger days, had an interesting strategy

for work and play. He worked for awhile at a high-paying job and saved

money, then took a vacation and did whatever he wanted; he could hang out at a coffee shop, read a book, sleep, eat, go for a walk, or travel to faraway places

by hopping on a plane or driving away in his car.

Usually, employers want workers

committed to long-term stability, so why did they tolerate his unusual behavior?

He was reliable, always showed up on time, and gave them a week's notice

before departing. But the main reason for their acceptance was the

quality of his work. He was one of the best welders in the city, performing

a valuable service that was in high demand, and doing it extremely well. He could

audition for a job, saying "give me a really tough welding challenge

and I'll show you how good I am." They did, he did, and they

hired

him.

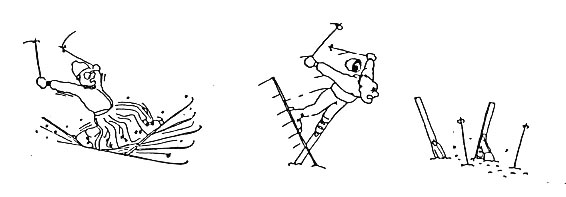

Like the welder, you can learn from both success and failure so you will continually improve. This principle can help you learn-and-improve in many areas of life, ranging from school exams and ski slopes to the workplace. You can learn from your mistakes, as when your exam is returned and for each wrong answer you ask "Why did I miss this?" and "How can I change-and-improve so the next time I'll get it correct?" And you can learn from your success, as when "I learned how to ski by doing it correctly, with high-quality practice, not by making mistakes." More commonly, you learn from both failures and success, as when you self-observe how you're performing on the job, and take time during the work-day (and at the end of a day, week, month, or year) to review what you've done. During these reviews it's important to be totally honest with yourself, fully acknowledging (with no denial) both positive and negative aspects of your own performance, so you can more accurately observe, evaluate, and adjust in order to do it better than before, by learning from the past and focusing in the present.

How

I Didn't Learn to Ski ( by Learning from Mistakes )

My first day of skiing!

I'm excited, but the rental skis worry me. They look much too long,

maybe uncontrollable? On the slope, fears come true quickly and I've

lost control, roaring down the slope yelling "Get out of my way!

I can't stop!" But soon I do stop — flying through the air sideways,

a floundering spin, a mighty bellyflop in icy snow. My boot bindings

grip like claws that won't release their captive, and the impact twists my

body into a painful pretzel. Several zoom-and-crash cycles later I'm

dazed, in a motionless heap at the foot of the mountain, wondering what I'm

doing, why, and if I dare to try again.

Even the ropetow brings disaster.

I fall down and wallow in the snow, pinned in place by my huge skis, and the

embarrassing dogpile begins, as skiers coming up the ropetow are, like dominoes

in a line, toppled by my sprawling carcass. Gosh, it sure is fun to

ski.

With time, some things improve. After

the first humorous (for onlookers) and terrifying (for me) trip down the crowded mountain,

my bindings are adjusted so I can bellyflop more safely. And I develop a

strategy of "leap and hit the ground rolling" to minimize ropetow

humiliation. But my skiing doesn't get much better so — wet and cold,

tired and discouraged — I retreat to the safety of the lodge.

How I Did

Learn to Ski ( Insight and Practice, Perseverance

and Flexibility )

The lodge break is wonderful, just what

I need for recovery. An hour later, after a nutritious lunch topped

off with delicious hot chocolate, I'm sitting near the fireplace in warm dry

clothes, feeling happy and adventurous again. A friend tells me

about another slope, one that can be reached by chairlift and is much less crowded, and I'm now feeling frisky and bold so I decide

to "go for it."

This time the ride up the mountain is exhilarating.

Instead of feeling the humiliation of causing a ropetow domino dogpile and being on the bottom, the lift carries me high above

the earth like a great soaring bird. Soon, while moving mainly across the hill (not mainly down it) with a rare feeling of control, I dare

to experiment — and the new experience inspires an insight! If I press

my ski edges against the snow a certain way, they "dig in."

This edging, combined with insights from other experiments — an "unweight and ski-swing" (a "jump a little so I can swing the skis around"

leg-ankle-foot movement) — produces a crude parallel turn that lets me zig-zag down the

slope in control, without runaway speed, and suddenly I can ski!

Continuing practice now brings rapidly

improving skill, and by day's end I'm feeling great. I still fall down

occasionally, but not often, and I'm learning from everything that happens,

both good and bad. And I have the confident hope that even better downhill

runs await me in the future. Skiing has become fun!

This experience illustrates two useful principles for learning:

1) Insight and Quality Practice: I learned how to ski by doing it correctly, with high-quality practice, not by making mistakes. There was no amazing improvement until I discovered the "unweight, ski-swing, ski-edge" tools for turning. This insight made my practicing effective so I could quickly develop improved skill: insight --> quality practice --> skill. Working as cooperative partners, insight and practice are a great team. Together, they're much better than either by itself.

2) Perseverance and Flexibility:

My morning ski runs weren't fun and I didn't learn much, but I kept trying

anyway, despite the risk of injury to body and pride. Eventually this

perseverance paid off. Because I refused to quit in response to frustrating

morning failures, I experienced the great joys of afternoon success.

/ But if I had continued practicing the old techniques over and

over, I never would have learned the new way to turn. Perseverance led

to opportunities for additional experience, but flexibility allowed the new

experience that produced insight and then improvement.

Perseverance and flexibility are contrasting

virtues, a complementary pair whose optimal balancing depends on aware understanding

(of yourself and your situation) and wise decisions. In each situation

you can ask, "Do I want to continue in the same direction or change course?"

Sometimes tenacious hard work is needed, and perseverance is rewarded.

Or it may be wise to be flexible, to recognize that what you've been doing

may not be the best approach and it's time to try something new.

Steps and Leaps

In many areas of life, much

of your improvement will come one step at a time. Each step you take

will prepare you for the next step as you make slow, steady progress.

But you can also travel in leaps. This is possible because many skills

are interdependent, which is bad news (if you haven't yet mastered an important

tool, everything you do suffers from this weakness) and good news (because

key insights can let you make rapid progress, as in my skiing experience).

If you consistently learn from experience

by searching for insight, your steps and leaps will soon produce a wonderful

transformation. You will find, increasingly often, that challenges

which earlier seemed impossible are becoming things you can now do with

ease.

The Joy of Thinking — it's

fun!

Personal goals for learning can include improving skills (like welding or thinking) and exploring ideas.

One powerful

motivating force is a curiosity about "how things work." We

like to solve mysteries. The joyful appreciation of a challenging

mystery and a clever solution is expressed in the following excerpts

from letters between two scientists who were intimately involved in the development

of quantum mechanics: Max Planck (who in 1900 opened the quantum era with

his mathematical description of blackbody radiation) and Erwin Schrödinger

(who in 1926 wrote and solved a "wave equation" to explain quantum

phenomena). Planck, writing to Schrödinger, says "I am reading your

paper in the way a curious child eagerly listens to the solution of a

riddle

with which he has struggled for a long time, and I rejoice over the beauties

that my eye discovers." Schrödinger replies by agreeing that "everything

resolves itself with unbelievable simplicity and unbelievable beauty,

everything

turns out exactly as one would wish, in a perfectly straightforward manner,

all by itself and without forcing." They struggled with a problem,

solved it, and were thrilled. It's fun to think and learn! / You can learn more about how

Planck and Schrodinger (plus Einstein & others) solved the mystery by learning to see our world from the fascinating perspective of micro-level quantum physics, where particles are waves, and waves are

particles.

You may not discover a basic principle of nature, like solving the mystery of quantum mechanics, but you can have your own "aha" moments when an idea (or a connection between previously independent ideas) suddenly becomes clear, when you find your own personal insights and you experience the joy of thinking-and-learning.

Forward-Looking Motivation

An attitude of intentional learning — of investing

extra mental effort, beyond what is required just to complete a task, with

the intention of achieving personal goals for learning — is a

problem solving approach to self-education because the goal is to transform

a current state of personal knowledge (including ideas and skills) into an

improved future state.

Effective intentional learning combines

an introspective access to the current state of one's own knowledge, the foresight

to envision a potentially useful state of improved knowledge that does not

exist now, a decision that this goal-state is desirable and is worth pursuing,

a plan for transforming the current state into the desired goal-state, and

a motivated willingness to invest the time and effort required to reach this

goal.

The use of knowledge can

be viewed from two perspectives: backward-reaching and forward-looking.

You can reach backward in time, to use now what you have learned in

the past. Or you can try to learn from current experience, motivated

by your forward-looking expectations that this knowledge will be useful in

the future.

In a forward-looking situation a learner

is anticipating the future use of an idea in a context that may be similar

(for basic application) or different (for application

involving transfer). When this occurs

an idea becomes linked, in the mind of a learner, to several contexts — including

situations imagined in the future — thus producing a bridge between now and

the future. This mental bridge can lead to improved retention (so knowledge is preserved) and application/transfer (so knowledge is more likely to

be used).

Intentional learning and

forward-looking application are closely related, and both strategies are activated

when a student wisely asks, "What can I learn now that will help me in

the future?"

So far,

our focus has been on the learner. But what about teachers? The following

section examines an important function of a teacher: to motivate students

so they will want to learn.

Motivational

Teamwork in Education (with students-and-teachers operating as a team)

What ideas and skills should students

learn?

Are the educational goals of a teacher (or a system of schools) worthy of the time invested by students and teachers?

Do students understand the goals, and want to achieve them? Of course,

goal-directed teaching is easier if students

are motivated by their own desires for goal-directed

learning, and if there is agreement about goals.

When worthy

goals are highly valued by students, the school experience is transformed

from a shallow game (of doing what the teacher wants, with the short-term

goal of avoiding trouble) into an exciting quest for knowledge in which the

ultimate goal is a better life. Instead of doing only what is required

to complete schoolwork tasks, students will invest extra mental effort

with

the intention of pursuing their own goals for learning. Why? Because

they are motivated by a forward-looking expectation that what they are learning

will be personally useful in the future, that it will improve their lives.

They will wisely ask, "What can I learn now that will help me in the

future?"

When teachers and students

share the same goals, education becomes a teamwork effort with an "us"

feeling. When students are highly motivated to learn, simply calling

attention to a learning opportunity is sufficient.

Why should students want to learn? Basically, students are motivated by activities they think are fun and/or useful. Of course, fun and utility, like beauty, are in the mind of a beholder. But in many situations,

persuasion by a teacher is helpful, to show students why they should want to learn

what is being taught.

Of course, this persuasion will be easier and more effective if, when teachers are designing their instruction, they try to search for goals and activities that connect with what students

want to learn. During activities designed to teach thinking skills,

if students are studying topics that connect with their personal interests,

they will think more willingly and participate more enthusiastically.

They will have fun, and they'll be preparing for the future. How?

If students are studying topics they find interesting and relevant, and there

is a forward-looking expectation that what they are learning in school will

be personally useful in the future, they will want to learn so they can improve

their own lives. A teacher can promote this attitude of internally motivated

learning by explaining how students can use "school knowledge" in

their lives outside the classroom.

For example, students will be more motivated

to improve their scientific thinking skills when they realize — because a

teacher calls it to their attention — that similar problem-solving methods

are used in science and in other areas of life,

in the design of familiar products, theories,

and strategies. The similarities between design and science, and the

advantages of a "design before science" approach, which lets students

begin with familiar skills so they can build on the foundation of what they

already know, are discussed in An

Introduction to Design.

a summary: An essential function of education, and a satisfying aspect of teaching, is to motivate students so they want to learn. Motivation can be inherent (to enjoy an interesting activity), external (to perform well on an exam), personal (to improve the long-term quality of life), and interpersonal (to impress fellow students or a teacher). Hopefully, students will discover that thinking is fun, and they will want to do it more often and more skillfully!

motivation in

home schools: In a traditional classroom, in a public

or private school, a teacher tries to produce a "community"

feeling with cooperative teamwork and a sharing of goals, as discussed

above. In home schooling, which offers the possibility of individually

customized educational goals and personalized instruction, it should be

easier to agree on goals and to enjoy the benefits that result from a

close teamwork between teacher and student.

External

sources of motivation, such as exams, which are a common part of the instructional

process in traditional settings, often serve valuable functions. But

personal motivations also offer benefits, as explained below.

Motivations:

External and Personal

An interesting question is,

"What are the relative effects of motivations that are external (focused

on getting rewards offered by others, with judgment by others) and personal

(focused on rewards that are internal, within a person, as judged by the person)?"

This is discussed in Dimensions of Thinking (Marzano, et al, 1988,

page 25):

Creative individuals look inwardly to themselves rather than outwardly to their peers to judge the validity of their work. ... Closely related to the locus of evaluation is the question of motivation. Perkins (1985) asserts that creativity involves intrinsic more than extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is manifested in many ways: avowed dedication, long hours, concern with craft, involvement with ideas, and most straightforwardly, resistance to distraction by extrinsic rewards such as higher income for a less creative kind of work. In fact, considerable evidence indicates that strong extrinsic motivation undermines intrinsic motivation (Amabile, 1983). Of course, this evidence is consistent with the discussion of attitudes about self in Chapter 2. Encouraging students to emphasize their success at tasks can eventually undermine self-esteem. Rather, we should help students to work more from their own internal locus of evaluation and encourage them to engage in tasks because of what they might learn or discover.

comments: Eventually, I'll find more information about this idea. For example, I want to know what the authors mean when they say that "encouraging students to emphasize their success at tasks can eventually undermine self-esteem." I'm sure there is a balance here, with some types of "encouragement to success" (done in some ways, in some amounts) producing beneficial effects, while other approaches to externally defined success, especially if carried to extremes, are detrimental. Also, can we make a sharp distinction between different motivations? Personal motivations, as discussed throughout this page, may include the hope of external rewards (employment as a welder,...) or interpersonal rewards (praise for skiing skill,...) in the future, with delayed (but externally oriented) gratification, so distinctions between types of rewards (inherent, external, personal, interpersonal) are not always distinct or clear. But it can still be useful to think about different aspects of educational motivation, about why we want to learn.

What's Next? — Motivations for Learning and Strategies for Learning are the foundations of education. But this

page is just a beginning, an introduction to a wide variety of fascinating

ideas. An exploration of these ideas continues in

the related pages below.

REFERENCES

Carl Bereiter & Marlene Scardamalia, 1989.

"Intentional Learning as a Goal of Instruction," in Knowing,

Learning, and Instruction, edited by L. Resnick. Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates: Hillsdale, New Jersey.

David Perkins & Gavriel Salomon, 1988.

"Teaching for Transfer," Educational Leadership 46, 22-32.

David Perkins, 1992. Smart Schools:

From Training Memories to Educating Minds. Free Press (Macmillan):

New York.

IDEAS — Bereiter & Scardamalia (1988) describe a principle of intentional learning; Perkins & Salomon (1988) suggest that the application and transfer of knowledge can be analyzed along two dimensions (backward-reaching or forward-looking, and high road or low road); and Perkins (1992) introduces a simple theory that "people learn much of what they have a reasonable opportunity and motivation to learn" and explains its implications for instruction.

CARTOONS — Frank Clark, 1982 — inspired by reading about

my skiing misadventures, he drew "a mighty bellyflop in icy snow." He also made Power Tools for Effective Learning & Cooperative Juggling and is now Creative Director of Square Tomato Advertising in Seattle.