![]()

![]()

Home

Topics

About Science & Faith

Apologetics

Archaeology &

Anthropology

Astronomy &

Cosmo

Bible & Science

Creation &

Evolution

Education

Environment

Ethics

Historical Studies

Mathematics

Origin of Life

Philosophy

Physical Science

Psychology &

Neur

Science &

Technology Ministry

Teaching

& Research

Worldview

Whole-Person

Education

Youth Page

Publications

JASA/PSCF

Articles

Book

Reviews

ASA/CSCA Newsletter

___________________ I shall argue that a Christian academic and scientific community ought to pursue science in its own way, starting from and taking for granted what we know as Christians.

(This suggestion suffers from the considerable disadvantage of being at present both unpopular and heretical; I shall argue, however, that it also has the considerable advantage of being correct.)

Now one objection to this suggestion is enshrined in the dictum that science done properly necessarily involves methodological naturalism or (as Basil Willey calls it) provisional atheism.

This is the idea that science, properly so-called, cannot involve religious belief or commitment.

My main aim in this paper is to explore, understand, discuss, and evaluate this claim and the arguments for it.

I

am painfully aware that what I have to say is tentative and incomplete,

no more than a series of suggestions for research programs in Christian

philosophy.

Alvin Plantinga--1997

________________________________________________________

Basic Philosophy

Books Dialogues Home

Papers

The Philosophy, Science, and Faith Page

(filos' o fe)

n., pl. phi los o phies. (Abbr. phil., philos.)

- The investigation of causes and laws underlying reality.

- Inquiry into the nature of things based on logical reasoning rather than empirical methods.

- The critique and analysis of fundamental beliefs as they come to be conceptualized and formulated.

- The synthesis of all learning.

- The science comprising logic, ethics, aesthetics, metaphysics, and epistemology.

We

are primarily interested with the contribution of philosophy to a

Christian View of Nature and the Scientific Enterprise

Enterprise

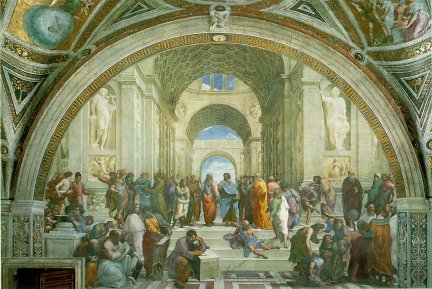

Raphael's "School of Athens" fresco in the Vatican

One way to dig into the subject is to examine some of the recent philosophical offerings in Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith (PSCF). The dialogues offer instructive ways to deal with hard questions.

Jitse M. van der Meer, "Ideology and Science," Reformed Academic, 16 August 2010 PDF The notion that not only facts but also personal and communal beliefs contribute to scientific knowledge has become commonplace. It raises two important questions. How can people with very different belief systems work together in science? Can scientific knowledge be trusted if it is shaped and sometimes distorted by beliefs operating in the background of science (background beliefs)? In this essay I explain why background beliefs are required for the construction of theories in science. I argue that background beliefs do not normally distort scientific knowledge because God created an objectively existing reality that resists distortion. Therefore, the background beliefs of scientists do not dictate the content of scientific knowledge. The conclusion is that people with different belief systems including Christians can work together in scientific research.

Discussion: Essentialism and Evolution (2012) --from BioLogos

Dr. Bruce A. Little part 1 part 2

Bruce A. Little introduces the concept of essentialism, suggesting that it is most consistent with the biblical idea of the fixity of species and constitutes a challenge to evolutionary origins of life on earth. Dr. Little also made the case that modern science has unjustifiably marginalized essentialism because it does not fit within a purely physical understanding of reality.

Response: Dr. Robert C. Bishop part 1 part 2

Robert A. Bishop begins the BioLogos response by tracing the decline of essentialism in Western philosophy and science, and suggests that essentialism is not the only (or the best) way for Christians to answer the question, “What does it mean to be human?” Dr. Bishop suggests that Trinitarian theology and the image of God are important, non-essentialist resources to help us think about the distinct place of humanity in creation.

...another friendly discussion

Roy Clouser, "Prospects for Theistic Science," PSCF 58 (March 2006): 1-15.

- Pierre Le Morvan, "Is Clouser's Definition of Religious Belief Itself Religiously Neutral?," PSCF 58 (March 2006): 16-17.

- Hans Halvorson, "Comments on Clouser's Claims for Theistic Science," PSCF 58 (March 2006): 18-19.

- Del Ratsch, "On Reducing Nearly Everything to Reductionism," PSCF 58 (March 2006): 20-22.

Roy Clouser, "Replies to the Comments of Le Morvan, Halvorson, and Ratzsch on "Prospects For Theistic Science," PSCF 58 (March 2006): 23-27.

Alvin Plantanga, Religion and Science Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Feb 20, 2007. "Modern western empirical science has surely been the most impressive intellectual development since the 16th century. Religion, of course, has been around for much longer, and is presently flourishing, perhaps as never before. (True, there is the thesis of secularism, according to which science and technology, on the one hand, and religion, on the other, are inversely related: as the former waxes, the latter wanes. Recent resurgences of religion and religious belief in many parts of the world, however, cast considerable doubt on this thesis.) The relation between these two great cultural forces has been tumultuous, many-faceted, and confusing. This entry will concentrate on the relation between science and the theistic religions: Christianity, Judaism, Islam and theistic varieties of Hinduism and Buddhism, where theism is the belief that there is an all-powerful, all-knowing perfectly good immaterial person who has created the world, has created human beings "in his own image," and to whom we owe worship, obedience and allegiance. There are many important issues and questions in this neighborhood; this entry concentrates on just a few. Perhaps the most salient question is whether the relation between religion and science is characterized by conflict or by concord. (Of course it is possible that there be both conflict and concord: conflict along certain dimensions, concord along others.) This question will be the central focus of what follows. Other important issues to be considered are the nature of religion, the nature of science, the epistemologies of science and, in particular, of religious belief, and the question how the latter figures into the (alleged or actual) conflict or concord between religion and science."--Abstract

Essay Review: Robert Prevost, "Athens Meets Jerusalem: Revelation for Philosophers." PSCF 61 (March 2009): 29.

Del Ratzsch, Science and Design (2006) Interviewed by the Galilean Library.

Kevin S. Seybold, "The Untidiness of Integration: John Staplton Hapgood," PSCF 57 (June 2005): 114-119.

Ben M. Carter, "Richard Dawkins and the Infected Mind," PSCF 57 (June 2005): 120-125.

J. P. Moreland, "A Christian Perspective on the Impact of Modern Science on the Philosophy of Mind," PSCF 55 (March 2003): 2-12.

Jack Collins, "Miracles, Intelligent Design, and God - of - the - Gaps," PSCF 55 (March 2003): 22-29.

Keith Miller, "The Similarity of Theory Testing in the Historical and Hard Sciences" PSCF 54 (June 2002): 119-123.

Del Ratzsch, "Cradled Science: Examining the Cosmos in the Context of Faith," Journal of Adventist Education 64 5 (2002): 9-12. (used by permission) An introduction to current philosophy by the Calvin College philosopher.

Dennis L. Feucht, "Determinism and the Semi-decidability of a Free Choice," PSCF 54 (September 1999): 158-160. Donald M. MacKay was a Scottish physicist, brain researcher, and contributor to the understanding of the relationship between science and Christian faith. He championed an argument that physical determinism does not negate freedom of the will. Just as Heisenberg's uncertainty principle reveals a basic physical limitation on the determinacy of the physical world, MacKay's argument has value in that it makes explicit a basic logical limitation on determinacy as it relates to self-conscious beings, or agents.

George L. Murphy, "Does the Trinity Play Dice?" PSCF 51 (March 1999): 18-25. The interpretation of quantum theory and its implications continue to be controversial. In this paper, we survey some issues raised in debates in order to pursue the belief that the God who is involved with the world in quantum phenomena is the Holy Trinity. Interpretations which emphasize participatory aspects of quantum theory are especially congenial to an understanding of divine action which centers on the Incarnation. In this light, we examine questions about reality, knowledge of the world, the role of chance, complementarity, material identity, and the entanglement of systems.

Kennell J. Touryan, "Are Truth Claims in Science Socially Constructed." PSCF 51 (June 1999): 102-107.

Robert T.

Pennock, "The

Prospects for a Theistic Science," PSCF 50

(September 1998): 205-209.

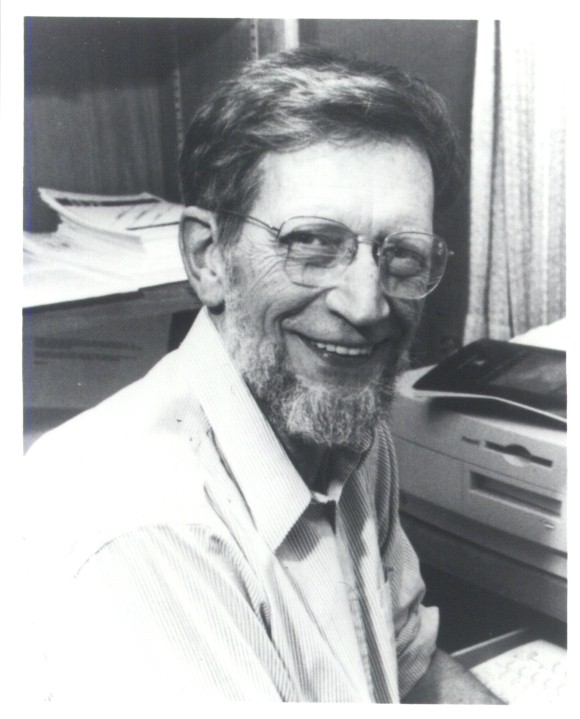

Alvin Plantinga

Alvin

Plantinga, "Methodological

Naturalism?" PSCF 49 (September

1997):143.

David

F. Siemends, Jr.,

"On

Moreland: Spurious Freedom, Mangled Science, Muddled Philosophy,"

PSCF 49 (September 1997): 196.

(September 1997): 196.

Alfred North Whitehead

Keith Abney, "Naturalism and Non-teleological Science: A Way to Resolve the Demarcation Problem Between Science and Non-science," PSCF 49 (September 1997): 162.

J. P. Moreland, "Complementarity, Agency Theory, and the God-of-the-Gaps," PSCF 49 (March 1997):2

Robert C. O'Connor, "Science on Trial: Exploring the Rationality of Methodological Naturalism," PSCF 49 (March 1997): 15.

Phillip E. Johnson, "The Religion of the Blind Watchmaker," PSCF 45 (March 1993): 46.- Discussion of the thesis of Walter R. Thorson in the March 2002 issue of PSCF

Thorson, Walter R., "Legitimacy and Scope of

Naturalismî in Science:

Part 1. Theological Basis for a Naturalistic Science, PSCF

54

(March 2002): 2.

[PDF]

Thorson, Walter R., "Legitimacy and Scope of

Naturalism in Science:

Part 2. Scope for New Scientific Paradigms," PSCF 54

(March 2002):

12.

[PDF]

Dembski, William A.. "Can Functional Logic Take the Place of

Intelligent

Design?" [Response to Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March

2002): 22.

[PDF]

Drees, Willem B., "Can We Reclaim One of the Stolen Words?"

[Response to Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002):

24.

[PDF]

Hawk, William, "Is God Transcendent or Immanent in Creation?"

[Response to Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002):

26.

[PDF]

Haarsma, Loren, "Can Many World Views Agree on Science?" [Response to

Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002): 28.

[PDF]

Crouch, Catherine H., "Is Scientism the Predominant Religion of

Scientists?

[Response to Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002):

30.

[PDF]

Finger, Thomas, "Is the Boundary Between Science and Theology

Distinct?" [Response to Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54

(March 2002):

32.

[PDF]

Bowman, Richard, "Can We Trust the Logic of Function?" [Response to

Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002): 34.

[PDF]

Miller, Elva B., "Does Design Tip the Scales?" [Response to Thorson

54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002): 35.

[PDF]

Vibert, Peter, "What Is Logic of Functional Organization? [Response to

Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002): 36.

[PDF]

Mills, Gordon C., "Are the Standards of Evidence Realistic? [Response

to

Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002): 37

[PDF]

Trenn, Thaddeus, "What Is the Deep Structure of Naturalism?"

[Response to Thorson 54.1] PSCF 54 (March 2002):

39.

[PDF]

Sire, James W., "Method or Metaphysics?" [Response to Thorson 54.1]

PSCF

54 (March 2002): 40.

[PDF]

Finally: Thorson Replies... ["Response to Dembski

et al." 54.1] 42

[PDF]

"Are Evangelical Scientists Practical Atheists?" ASA scientists answer the charge

Has Science Killed God? Prof. Alister McGrath

This paper explores the aggressively atheist reading of the natural sciences associated with Richard Dawkins, raising serious questions about its intellectual plausibility and evidential foundation. Has the former populariser of science now become little more than an anti-religious propagandist, using science in the crudest of ways to combat religion, ignoring the obvious fact that so many scientists are religious believers? Dawkins’ atheism seems to be tacked onto his science with intellectual Velcro, lacking the rigorous evidential basis that one might expect from an advocate of the scientific method.--Faraday Institute

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Outstanding collection of materials regularly updated. (a bit slow to upload)

Jitse M. van der Meer ed., Facets of Faith & Science, Vol 1: Historiography and Modes of Interaction (New York: University Press of America, 1996).

Dal Ratzsch, Philosophy of Science (Downers Grove IL: InterVarsity Press, 1986).

Last Entry:7/27/2012

![]()